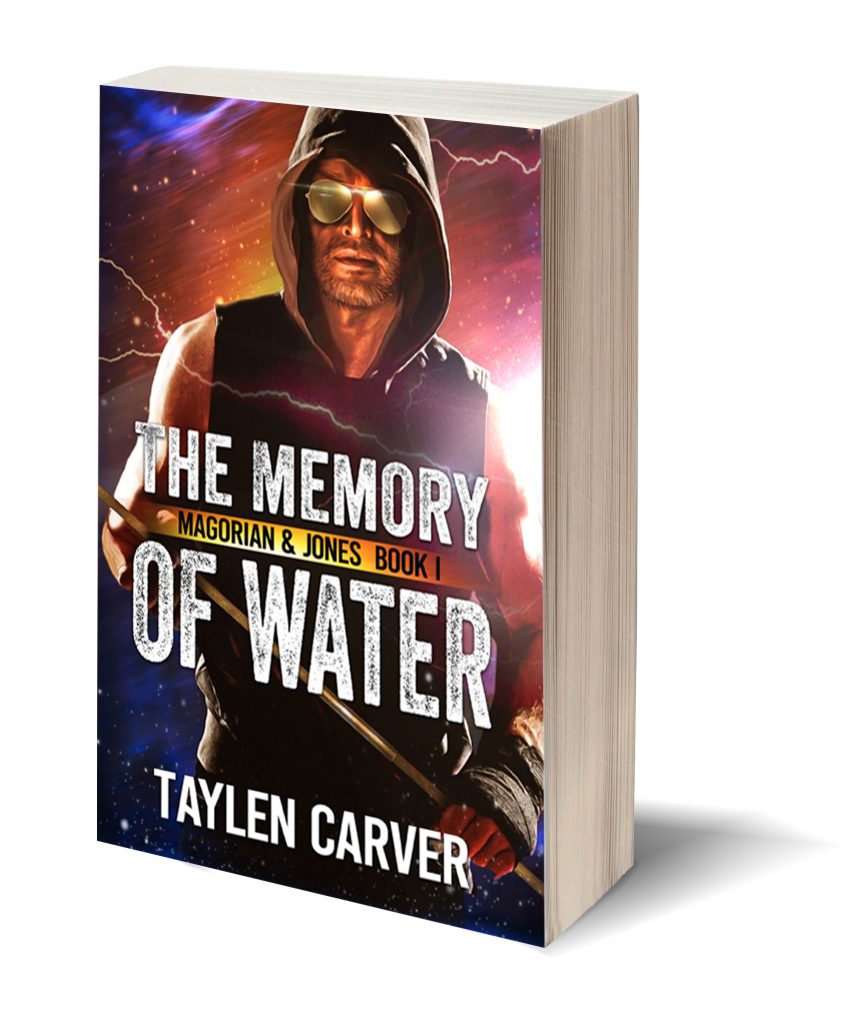

THE MEMORY OF WATER by Taylen Carver

Magorian & Jones 1.0

Urban Fantasy Novel

More books by Taylen Carver

Click here to read the reviews

Click here to read an excerpt

When a skeptical doctor teams up with an honest-to-god wizard on a quest for an ancient and powerful manuscript, enemies lurk around every corner.

Dr. Radford Michael Jones has dedicated his life to the treatment of the goblyns, fae, dragons, sirens and even more races which humans call the Errata.

Frustrated in his attempts to treat the newest race to emerge, Jones consults Magorian, whom the Errata call the first and only wizard of the millennium, his skepticism at full throttle.

Benjamin Magorian III has no time for the Errata, who did not spend a lifetime learning magic as he has done. He has even less time for Dr. Jones, who doesn’t respect his work. Yet his healing skills are needed.

Magorian and Jones’ combined talents embroil them in the search for an ancient manuscript, the Book of Morcant, which may hold the answers both of them so desperately need.

But they are not the only ones who seek the records of the last great wizard to walk upon the world…

The Memory of Water is part of the urban fantasy series, Magorian & Jones, by Taylen Carver.

The Magorian & Jones series:

1.0: The Memory of Water

2.0: The Triumph of Felix

3.0: The Shield of Agrona

3.5: The Wizard Must Be Stopped

4.0: The Rivers Ran Red

5.0: The Divine and Deadly

5.5: Magorian & Jones Boxed Series Set

Urban Fantasy Novel

This series is also available as a Special Bundle

{Also see: Urban Fantasy, Novels}

BUY FROM STORIES RULE PRESS

CAD $27.99

BUY PAPERBACK

FROM STORIES RULE PRESS

Buy from SRP and earn purchase points!

Electronic book, compatible with all reading devices. Book can be read on all devices and apps. [More info]

BUY FROM YOUR FAVOURITE BOOKSELLER

PRINT:

AMAZON

BARNES & NOBLE

BLACKWELL’S

Reviews

Submit your review | |

I read a lot of great books this year, but this one topped them all!! Where to start? The story is unique- people turning in fairy tale creatures- and two damaged heroes with flaws who actually don´t want to be world savers. On top a gripping story with a lot of twist and turns. I couldn´t put the book down, so I finished it in two days and started reading the next in this series „The Triumph of Felix“

| Bookmark on Bookbub | Bookmark on Goodreads |

All prices are in CAD

Electronic book, compatible with all reading devices. Book can be read on all devices and apps. [More info]

ePub or Mobi format files provided.

You will receive an email from BookFunnel with the download links once your transaction has been processed. (For pre-orders, the download link will be emailed to you on the release date.)

BookFunnel will assist with any download issues. Click the Need Help? link at the top right of the download page.

You may also like…

| Continue browsing books | Jump back to top of page |

Excerpt

EXCERPT FROM THE MEMORY OF WATER

COPYRIGHT © TAYLEN CARVER 2020

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Cornwall

A group of Errata crouched at the far end of the beach, out of speaking distance of the humans soaking up the sun, including my family, which was closest. I measured the Errata as I flapped the blanket and spread it across the sand under the postage stamp-sized piece of shade the cliff provided. Soon, even that would be gone, for the sun was swinging around to the midday peak. As I laid out the blanket to maximize the shade, I watched them from the corner of my eye.

They were ignoring us, their heads together in a tight little group, which was normal. But I would still monitor them. I, more than anyone else in the world, knew what they were capable of.

Ffraid had volunteered to fight with the umbrella. As she is at least twice as smart as me, I didn’t argue when she grabbed the dusty thing out of the boot and tucked it under her arm like a Sergeant Major’s swagger stick.

The children jumped about, both because of the hot sand and because of the beckoning water.

“I want to go in!” Gwen said impatiently. “It’s my birthday.”

“It’s your father’s birthday, too, Gwendolyn,” Ffraid reminded her. “Stop nagging him.”

“It was an observation of my state of mind,” Gwen shot back. She had turned nine today, and I was already wondering how we would keep her adequately occupied with normal schooling, or if we should find an advanced program for her.

“Da, want to swim,” Olwen lisped. He had the sweetest nature of the three of them, but even he was impatient.

“Very well,” I told them, and held up a finger. “The rule, please?”

“Only up to my knees,” Heulwen parroted. Gwen nodded. Olwen just looked grave. The waves were tiny, but they were his first.

“Go, go!” Ffraid told them, and shooed them toward the water. “Gwen, hold Olwen’s hand, please!”

Gwen took Olwen’s pudgy hand and the three ran toward the water with shrieks and little leaps.

“It’s far too hot for such energy,” I said, lowering myself to the tartan blanket.

Ffraid dropped onto the blanket beside me and glared up at the umbrella, daring it to close upon us.

I mentally urged it to behave itself. The consequences of defying my wife weren’t worth it.

Fraid shaded her eyes against the glare of the sun on the water and looked at me, her eyes narrowed a little. “Are they dangerous, Michael?” She had switched to Welsh, which was unlikely to be understood by anyone around us. The closest humans was the family of three to my right, ten yards away.

I glanced at the Errata, away to the left, close by the curving end of the bay, where the beach narrowed to a short point of salt and brown seaweed encrusted rocks, before turning into the next bay. “They’re enjoying a day on the beach, too,” I said. “There’s humans among them,” I added, spotting the ghostly flesh of the arms of a typical Englishman without his pullover.

Ffraid studied them, making it look casual. She wasn’t the only human on the narrow beach sending them furtive glances. “Aren’t those…the ones with the dragonfly wings…what do you call them?”

“Water leapers,” I said. “Don’t call them dragonflies to their faces.”

“I won’t,” she murmured, turning her gaze back to the children. They were still shrieking, splashing each other and kicking up spray. Her mouth softened into a near-smile.

Then she glanced at me and lowered her hand. “Would it help if we found another beach?”

I jumped, guilt touching me. “No…no, we’re here now.”

“Godrevy is a humans-only beach,” she said. Her expression was nonjudgemental. “It’s not far from here.”

Her perfectly reasonable tone made me squirm. It always did. I shook my head. “That would be…” I hunched my shoulders. “Rude,” I finished.

“You mean, they’d notice us leaving,” Ffraid interpreted.

That made me even more uncomfortable. “Let’s change the subject.”

“Very well.” She crossed her legs, displaying shapely thighs and far too much midriff between the open front of her shirt. With her hair loose, she looked like a twenty-year-old. Anyone seeing her now in cheesecloth and a bikini would be taken aback to know she was Dame Ffraid Hyledd-Jones OBE, Oxford Professor, theoretical physicist, and mother of three. My three.

I glanced at the three in the water. “We should put sunscreen lotion on them. They’ll burn far too quickly, today.”

“Skin burns more quickly when it’s overcast,” Ffraid replied, reaching for the big bag that held lunch, among other things. “And you’re changing the subject.”

“You agreed we should.”

“I agreed we should stop talking about moving to another beach. I did not agree we should stop talking about the subject which came next.”

“You didn’t say anything.”

“But you know what I was about to say.”

I did. But to admit it would draw us even closer to the bloody subject.

“You’re watching them even now,” Ffraid added softly, making me jump once more. Because, damn it all, I had been studying them over her shoulder. “Dr. Jones, you need to take the day off. It is your birthday.”

“Yes,” I said, making my tone firm.

“Yes?” She said it flatly, confirming that she had heard me correctly.

“Yes, I’m still thinking about the offer.”

“It would be honourable work, Michael.”

“But it is in Spain,” I objected. “I would be uprooting—”

She held up her hand. “You must go where the work takes you.”

“And your work is here.”

“I can think about dark matter anywhere. That’s what ‘theoretical’ means.”

I knew—just as she did—that it wasn’t nearly as simple as that. But for some reason, Ffraid was pressing me to take the United Nations contract to run the refugee camp that was being formed in Toledo. I’d be working with the Errata there, and directing the management of the camp.

“You were the first doctor to deal with a phasing Errata–”

“It is called entering an active phase,” I corrected her stiffly. “It appals me that everyone uses such slang—especially you. It would be like me talking about hyperspace.”

Ffraid didn’t apologize. She didn’t flinch at my mention of science fiction jargon, as she normally did. Her jaw flexed. That should have warned me, but it didn’t. “You keep telling me no one knows very much about the Errata, or the Tutu virus, or how it all works. Only, if there was a list of international experts on the Errata, you would be on it, Michael. You must continue your work. You must learn everything you can about the virus.”

There was a strange note in her voice I had never heard before. “I think I’ve missed something,” I said, puzzled. “I thought we were talking about me.”

Ffraid’s gaze flitted away from mine, and my surprise increased. She was never unable to look me directly in the eye.

“Fraid?” I coaxed, keeping my voice down.

She closed her eyes and drew in a breath. I watched her gather her usual super-human courage together. Her gaze came back to me once more. “You don’t understand—how could you? You are always hip-deep among them, immersed in the facts as they are discovered, right on the very edge of the event-horizon.”

I understood the analogy, even though the physics of black holes were completely beyond me. “And I share everything with you. You know as much as I do about them–”

“Except for what we will become!” Ffraid cried softly, her voice husky with impending tears.

Dismayed, I struggled to find something to say. “But you didn’t get the virus,” I said slowly.

“The children did!” Ffraid closed her hand into a knuckle-bleaching fist. “And I could have caught it and been asymptomatic. So might you! How can we know? It goes dormant and hidden, until it shifts to active and then…” She stared at our three children playing in the wavelets, her eyes glittering.

“Not everyone goes through the active phase.” It was a pathetic attempt to calm her. I felt stupid even saying it, but I always felt helpless when she cried. I could count on one hand the times Fraid had cried, and they had all left me feeling this abysmal sense of uselessness. If my incredibly smart, Nobel laureate wife could not find answers, how on earth was I supposed to?

Yet when she cried, I wanted to fix things for her. So I gave her the equivalent of a there-there pat on the head.

Ffraid rightfully tossed it straight back at me. “You don’t know that! No one knows anything, you said. You know a thimbleful more than most, but you don’t know. You can’t tell me we won’t end up like them!” She shot her hand out to point at the dozen Errata sitting on bare sand, their backs to all the humans.

It was only then I thought to wonder how long she had been building up to this. And a secondary thought made me glance to the right, to the humans quietly enjoying their day while pretending the Errata were not there at all. How many other mothers, parents, brothers, sisters, children, lived with this quiet dread? This waiting?

I made myself look at Ffraid. “There are no guarantees,” I made myself say. “None. There are no patterns we’ve discerned. Not yet.” I gave her a scientific principal she would understand. “There isn’t a large enough data set to even begin to guess.”

She nodded, and her tears spilled. “But you do know that the virus doesn’t shift along DNA patterns. If I shift…if I phase, then I might become a…a water leaper. And Gwen might become…” She choked and put her face in her hands. “An orc!” Her voice was muffled, and filled with dread.

I was smart enough to not correct her terminology, this time. Orc was the epithet everyone used for the goblyns. I also didn’t tell her I thought there was a goblyn among the Errata sitting behind her, staying low and out of sight. She was upset enough already.

I picked up her hand. “Ffraid, listen. It doesn’t matter. None of it matters. I don’t care if you…if you phase. I don’t care if we all phase, and I don’t care what we become. It doesn’t matter. Do you understand?”

Ffraid shook her head, trying to hide her blotchy face with one hand. Denial.

I tugged her hand. “Look behind you,” I said, lowering my voice, even though we were still using Welsh. “Really look at them. There are three water leapers. There is at least one dwarf and I even think there is an angel. And if they’re this close to the water, the avanc who owns this section of the sea likely has his mate here, too. But do you see, Ffraid? There are all kinds among them…and they’re together.”

Ffraid gave a great sniff, then lifted a corner of the cheesecloth shirt and wiped her face. When it was quite dry, but still red, she looked at me. “Don’t you wonder what will happen to you? Aren’t you…afraid?”

I drew in a breath. Let it out. “When I let myself think of it, yes, I’m afraid,” I said truthfully. “But there is nothing we can do, except deal with whatever happens, when it happens.”

“And look for answers in the meantime,” she whispered.

I frowned.

Fraid gave me a stiff smile. “They found Gordy in his bed, yesterday. Sleeping pills.”

My jaw slackened. I stared at her, my heart thudding, as it all shifted and came together. While I pulled my wits back together, Ffraid turned toward the water, lifted her chin and her voice. “Gwen! Heuleg! Olwen! Come back here!” She used English, as the children were not comfortable with Welsh.

Gordon Howard was—had been–the dean of physics and Ffraid’s doctoral advisor. He’d walked her up the aisle, for Ffraid was without family just as I nearly was. He was a Scotch man, and spent all his spare time in a pocket handkerchief-sized garden at the back of his cottage in Godstow.

And he was the third professor in her department who had chosen to end matters now, who could not face waiting and wondering…

The children took not a bit of notice of Ffraid’s call, so she added, “Right this moment!” Her tone was more convincing than the words. We all knew that tone.

The three stepped reluctantly out of the water and trudged up the beach, dripping and breathing hard, their eyes shining. Even Olwen was dancing about with joy.

Ffraid took Olwen’s arm, tugged him closer to her. She pulled out the very large bottle of sunscreen lotion and uncapped it.

I beckoned Gwen toward me. “Turn around, let me reach your back.”

The squealing screams were distant and soft and I’d heard them so many times before that at first, I didn’t register the significance of them. I was too busy plucking Gwen’s wet, black locks from her back.

“Michael…!” Ffraid said softly. Her urgent tone did snag my attention. I looked up.

Ffraid looked at the Errata, then back at me.

The Errata were clustered in a tight group. I saw a pale foot kick out from among their legs, the flesh white from too much time spent inside. An arm flailed. The low grunting sounded again and this time I consciously registered it.

I got to my feet. “You three, stay with your mother,” I told Gwen, Heuleg and Olwen.

“Is that…is one of them phasing?” Ffraid asked in Welsh.

“Yes, I think so. I should help.”

She nodded. “Yes, you must.”

I was already sorting through what supplies and instruments I had in my kit in the car, as I walked over to the thick glob of Errata. “Let me through, please. I’m a doctor. I can help.”

The man on the sand was writhing, his contortions kicking up clouds of fine white sand. He looked human, but he wouldn’t for much longer.

Everyone around him hovered with their hands out, as if they were reaching to help. Only, they had no idea what to do to help him.

I yanked on the nearest shoulder, to make way for myself. A white wing snapped out in surprise and I ducked away from the thick upper edge. The angel looked over her shoulder.

“I’m a doctor,” I told her. “I can help.”

She looked troubled. “You know ‘ow to fix…us?” Her eyes were crystalline and beautiful, as all angels were. The expression in them was troubled.

I ducked the direct answer, which wouldn’t reassure her. “I’ve had a great deal of experience. Let me through.”

She brought her wings back in and folded them against her back. “He just started to…to scream ‘n to squirm.” Her accent was east London and thick. She tapped the arm of the water leaper next to her and they both shuffled out of the way.

“He is moving into active phase,” I told them. “Although I’ve never seen it come on so fast. There is usually a few days of fever…”

“’e was sick last week,” one of the other leapers said. “Moanin’ and groanin’. Then ‘e got better.”

“Hmm…” I said diplomatically. No one “got better” when they moved into active phase. They sickened, changed, or died. I knelt in the sand next to the writhing man. “The shift was delayed,” I murmured, studying his facial features. I absorbed the details, cataloguing them. I looked up at the leaper hovering over me. “My car is in the carpark at the top of the cliff. The white Mercedes. There is a Gladstone bag in the back of the boot. You can open the boot from the dashboard. We left the windows down because of the heat.”

The leaper nodded. Then she threw herself up into the air. Her gossamer wings spread with a soft snap and worked hard with the characteristic fluttering sound water leapers made when they flew. She lifted up in the air.

Farther along the beach, I heard gasps and cries of alarm as the humans saw her take flight.

I ignored them and instead studied my patient. He was kicking, thrusting and making harsh tearing sounds at the back of the throat. His eyes were screwed shut.

I frowned. If he had passed through the fever stage and avoided developing meningitis as so many of them did, then he should not be in such severe pain now.

I examined the way he was holding his eyes so tightly closed and the truth occurred to me—only it was too late.

He screamed, a very human sound, and the last he would make as a human, then threw his head back and howled. It was a guttural, deep sound, for his vocal chords were shifting.

Along the beach, I heard echoing gasps and horror-filled murmurs.

The Errata around me shifted on their feet, alarmed.

“Please, please, ‘elp him,” the angel murmured. Agony twisted her voice.

She would not personally remember the pain of her own phase-shift. None of them did.

“It will pass,” I assured her. “But we must get him out of the sun–”

The soon-to-be goblyn howled again, cutting me off. He straightened, rigid with pain.

The ground beneath us vibrated and began to shake, almost exactly like an earthquake.

Even the Errata moved away, their eyes widening. I looked between them for the black face and black tusks of the goblyn I knew was lurking behind them. I saw his red-rimmed eyes. “Control his power!” I told the goblyn sharply. “He cannot—not yet!”

The goblyn crouched down on the other side of my patient. He put his hand, with the thickly ridged, black epidermis on the back, on the shoulder of his new brother. “’ugh…’ugh!” He shook.

“He can’t hear you,” I told the goblyn.

“I can’t stop ‘im,” the goblyn replied. “Not in the sun, not out ‘ere.”

“If we get him inside, then?”

“Maybe…” the goblyn said. “If it’s dark, like.”

I put my hand out as the ground beneath me seemed to shrug and try to toss me aside.

A bone-deep cracking sounded.

Then the world paused, for one last shining moment. Even Hugh grew still.

We looked at each other.

“What was that?” one of them breathed, as if they were too afraid to speak any louder.

A man screamed, behind us.

“The cliff!! The cliff!”

I leapt to my feet and whirled at the same time, my heart racing. I saw something that my brain refused to process properly, not until many long black days later.

A massive portion of the cliff had cracked and was falling away from the land behind it. It was as if a giant had cleaved an axe into the land above, and now the severed section was falling away.

It fell with horrible slowness. It fell far too fast for me, with my pitiful human reactions, to respond.

“Ffraid!” My shout tore at my throat. I threw out my hand, as if that would shove my wife and my children far away from the shade at the foot of the cliff. Ffraid had Olwen on her hip as she slogged through the sand, with Heuleg’s hand in hers, while screaming at Gwen to run.

The goblyn leapt into a hard, driving sprint across the sand, as if it was a smooth running track beneath his thick feet. As he could control the earth, it possibly was hard track beneath each heavy foot. He raced toward them, a powerful, squat figure in jeans and teeshirt, moving with inhuman speed.

Even he was not fast enough. The cliff dropped like a broad shiv, driving into the soft beach beneath. The top half of cliff-face crumbled at the jarring impact with the land and spewed across the narrow beach and into the wavelets where my children had been playing only a few moments ago.

Then everything grew still once more. Very still.