From the SRP Editor blog:

One of the most common mistakes I see in fiction—especially from newer writers—is the “reasonable villain.” You know the type: a bad guy who’s dangerous but not too dangerous, strong but not too strong, clever but still just dumb enough for the hero to outwit by the end of Act Three.

Writers think they’re being smart—making things “believable.” What they’re actually doing is draining the tension right out of their story.

Because here’s the truth: A seemingly unstoppable antagonist is the best gift you can give your story.

The David and Goliath Principle

Let’s go back to where it all started: David and Goliath.

If Goliath had been five-foot-six and mildly cranky, that story would’ve vanished into the sands of history. Instead, we remember it because the odds were ridiculous. A boy with a sling faced a giant armed to the teeth—and won.

The sheer mismatch made the victory meaningful. The greater the power imbalance, the higher the stakes, and the more satisfying the triumph.

That’s the blueprint every good story still follows today.

When the Machines Rise: Sarah Connor vs. The Terminator

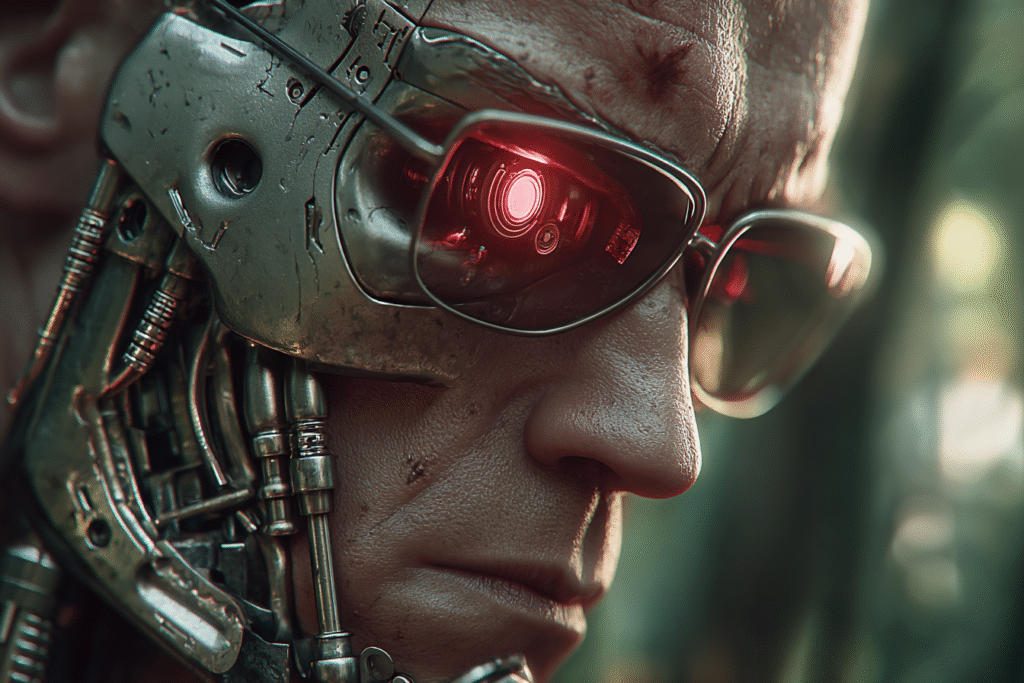

James Cameron understood this perfectly. In The Terminator, Sarah Connor starts as a terrified waitress being hunted by an unkillable metal monster from the future. The Terminator doesn’t feel fear, fatigue, or remorse. It just keeps coming.

And because of that, we care.

Watching Sarah go from helpless to hardened, from prey to predator, gives the movie its soul. Her victory isn’t easy, tidy, or even complete—but it feels earned. The unstoppable force met an unbreakable will.

If the Terminator had been a bumbling assassin or just a grumpy guy with a grudge, Sarah’s transformation wouldn’t matter. The greatness of her arc depends entirely on the scale of the threat she faces.

Resistance Is Futile—Or Is It?

Now, take Star Trek: The Next Generation. The Borg aren’t just villains; they’re a collective nightmare. Cold, logical, relentless—everything the Federation isn’t. And at their heart lies one of the most human characters in science fiction: Captain Jean-Luc Picard.

When the Borg assimilate him into Locutus, they don’t just threaten his life—they strip away his identity. The conflict isn’t just physical, it’s existential. His fight to regain himself and face the same enemy later, in First Contact, lands precisely because the Borg are terrifyingly powerful.

If Picard had faced a mediocre space pirate instead of the embodiment of dehumanizing conformity, we’d have forgotten him decades ago.

Why It Works

An overwhelmingly strong antagonist forces your protagonist to dig deep. They can’t rely on luck or convenience—they have to evolve. The villain’s power defines the hero’s growth.

Readers want to see characters pushed past their limits, stripped down to what really makes them them. That’s where emotion lives. That’s where catharsis happens.

A villain who’s too easy to defeat isn’t merciful to your protagonist—it’s cruel to your readers.

So Go Ahead—Stack the Deck

When you sit down to write your next story, don’t make things fair.

Make them impossible.

Give your hero an adversary who seems unbeatable, unkillable, unbreakable.

And then make them find a way to win anyway.

That’s how you turn a story from “good” into legendary.

SRP Editor’s Note

If your hero’s not sweating, your reader’s not turning pages. Give them a villain worth fearing—and you’ll give your audience a story worth remembering.

— Mark

Mark Posey

SRP Author and thriller writer.

Mark writes thrillers for readers who don’t mind a little dirt under the nails — stories with emotional weight, lean prose, and characters who rarely do the right thing for the right reason. His work lives somewhere between noir, revenge fantasy, and literary grit, though he avoids calling it any of those because that sounds like marketing.

When he’s not writing fiction, Mark also works as a professional editor and story consultant. His editing blog offers straight talk for indie and traditionally published authors alike — especially the ones who are tired of being told to “find their voice” by people who can’t define what voice is.

He believes in clarity over cleverness, clean narrative over trend-chasing, and that semicolons are fine, but you probably don’t need as many as you think.

He lives in Canada, which explains the politeness, but not the sarcasm.

You can find him online at MarkPoseyAuthor.com, where he blogs about writing, editing, story structure, and whatever else is on fire this week. His books are published through Stories Rule Press, an independent publisher of genre fiction with strong characters and sharp writing.