From the SRP Editor blog:

Writers like to talk about word counts. Fifty thousand words for NaNoWriMo, eighty thousand for a mystery, one hundred and twenty thousand for an epic fantasy. It’s as if stacking words end to end somehow guarantees a novel.

It doesn’t.

A novel is not a pile of words—it’s a sequence of scenes. And scenes are where the magic happens. They’re the building blocks of story structure, the smallest meaningful unit of narrative. If you can’t write a scene well, you’re going to have trouble writing a good novel, no matter how beautiful your prose or how clever your premise.

Writers who’ve studied craft giants like Robert McKee (Story) or Shawn Coyne (The Story Grid) know that scenes aren’t just little vignettes of people talking or doing things. They’re mini-stories unto themselves, each with its own internal architecture. When you understand how to build one properly, your entire novel gains momentum, clarity, and emotional punch.

Let’s take a look at the essential components of a strong scene.

1. The Inciting Incident

Every scene needs something to happen—something that throws the protagonist off balance and demands a response. It doesn’t have to be an explosion or a corpse on the floor (though those are always fun). It can be as small as an unexpected question or a subtle emotional shift. What matters is that it disrupts the status quo and forces a choice or reaction.

2. Rising Complications

Once the scene is set in motion, things should get more difficult. Obstacles arise. Stakes increase. Information is revealed that changes how the characters—and the reader—understand what’s going on. A scene without complications is flat; it coasts instead of climbs. You want pressure building toward something that must give.

3. The Crisis

The crisis is the point of decision—the moment when the protagonist faces a dilemma that can’t be ignored. Coyne calls this the “best bad choice” or the “lesser of two evils.” The character must make a choice, and that choice defines them. If there’s no meaningful decision, the scene will likely feel pointless, no matter how well written it is.

4. The Climax

This is where the character acts (or chooses not to act, which is also a choice). The climax is the visible or emotional peak of the scene, the moment the reader’s anticipation pays off. It’s where we see what the character is made of—or at least what they think they’re made of.

5. The Resolution

Every scene needs a moment of release, a beat that lets the reader feel the consequences of the climax. What changed? What was gained or lost? How does this outcome push the story forward or deepen our understanding of the character? If nothing has shifted by the end, you might not have a complete scene—you might have just filled some space.

Moving the Story Forward (or Revealing Character—Preferably Both)

A scene that doesn’t change something—whether plot, emotion, or knowledge—is a speed bump. Too many of those, and readers start checking their phones. Each scene should either move the story forward or reveal character—and ideally, do both. If it doesn’t, it’s time to break out the red pen.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

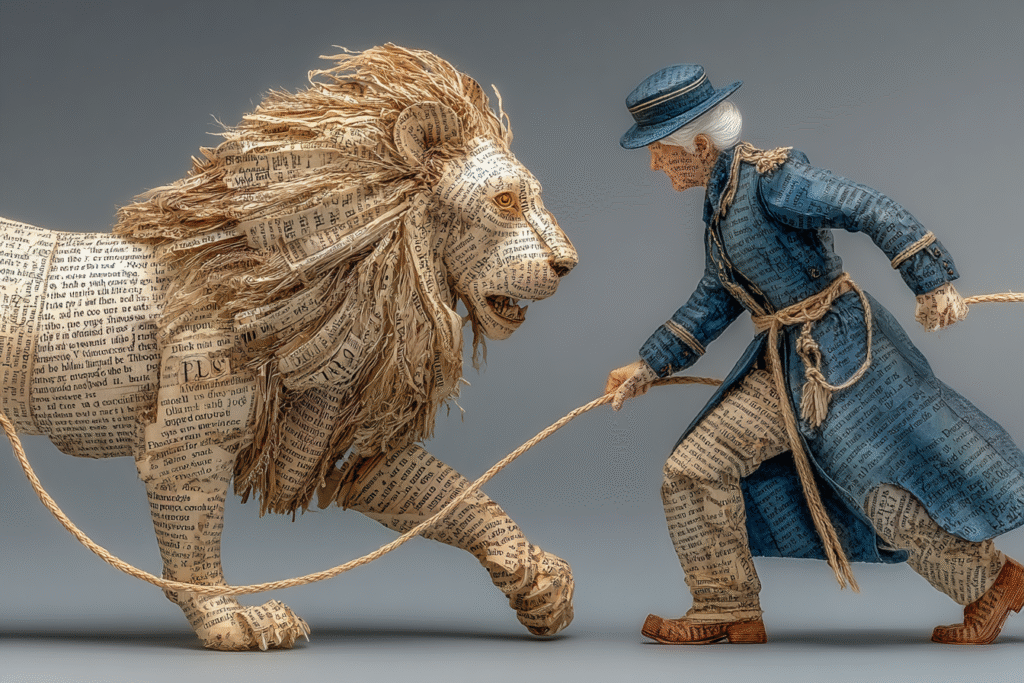

In an era when anyone can upload a novel to an online store in an afternoon, it’s tempting to believe that enthusiasm and output are enough. “I’ll write what I want!” has become a kind of creative battle cry. And that’s fine—until the reviews roll in and readers quietly move on to something that’s better built.

The writers who stand out—the ones whose books stick—are those who understand the craft beneath the passion. They build solid scenes that grip the reader, page after page. They know how to turn a sequence of moments into a chain of meaning.

Writing well isn’t about word count. It’s about scene count. Learn to write a powerful scene, and you’ll have the foundation for a powerful novel.

At Stories Rule Press, we see this all the time: strong ideas buried under weak scenes, or brilliant characters trapped in flat storytelling. The difference between a draft and a publishable novel often comes down to this one skill—scene craft. Nail that, and everything else starts to fall into place. And if you ever want a second pair of eyes to see how your scenes are holding up, well… that’s exactly what we do.

Email me at ed****@**************ss.com and I can tell you all about it.

Mark Posey

SRP Author and thriller writer.

Mark writes thrillers for readers who don’t mind a little dirt under the nails — stories with emotional weight, lean prose, and characters who rarely do the right thing for the right reason. His work lives somewhere between noir, revenge fantasy, and literary grit, though he avoids calling it any of those because that sounds like marketing.

When he’s not writing fiction, Mark also works as a professional editor and story consultant. His editing blog offers straight talk for indie and traditionally published authors alike — especially the ones who are tired of being told to “find their voice” by people who can’t define what voice is.

He believes in clarity over cleverness, clean narrative over trend-chasing, and that semicolons are fine, but you probably don’t need as many as you think.

He lives in Canada, which explains the politeness, but not the sarcasm.

You can find him online at MarkPoseyAuthor.com, where he blogs about writing, editing, story structure, and whatever else is on fire this week. His books are published through Stories Rule Press, an independent publisher of genre fiction with strong characters and sharp writing.